Yesterday, April 29, 2025, we had the pleasure of meeting various rangers, environmental agents, and other professionals specialized in rivers and fluvial connectivity from the Xunta de Galicia (Department of the Environment), and basin management organisations such as Augas de Galicia and the Miño-Sil Hydrographic Confederation.

We began the day by presenting the FREEFLOW project, followed by visits to the Couso weir and the Ximonde biological station.

Project FREEFLOW seminar

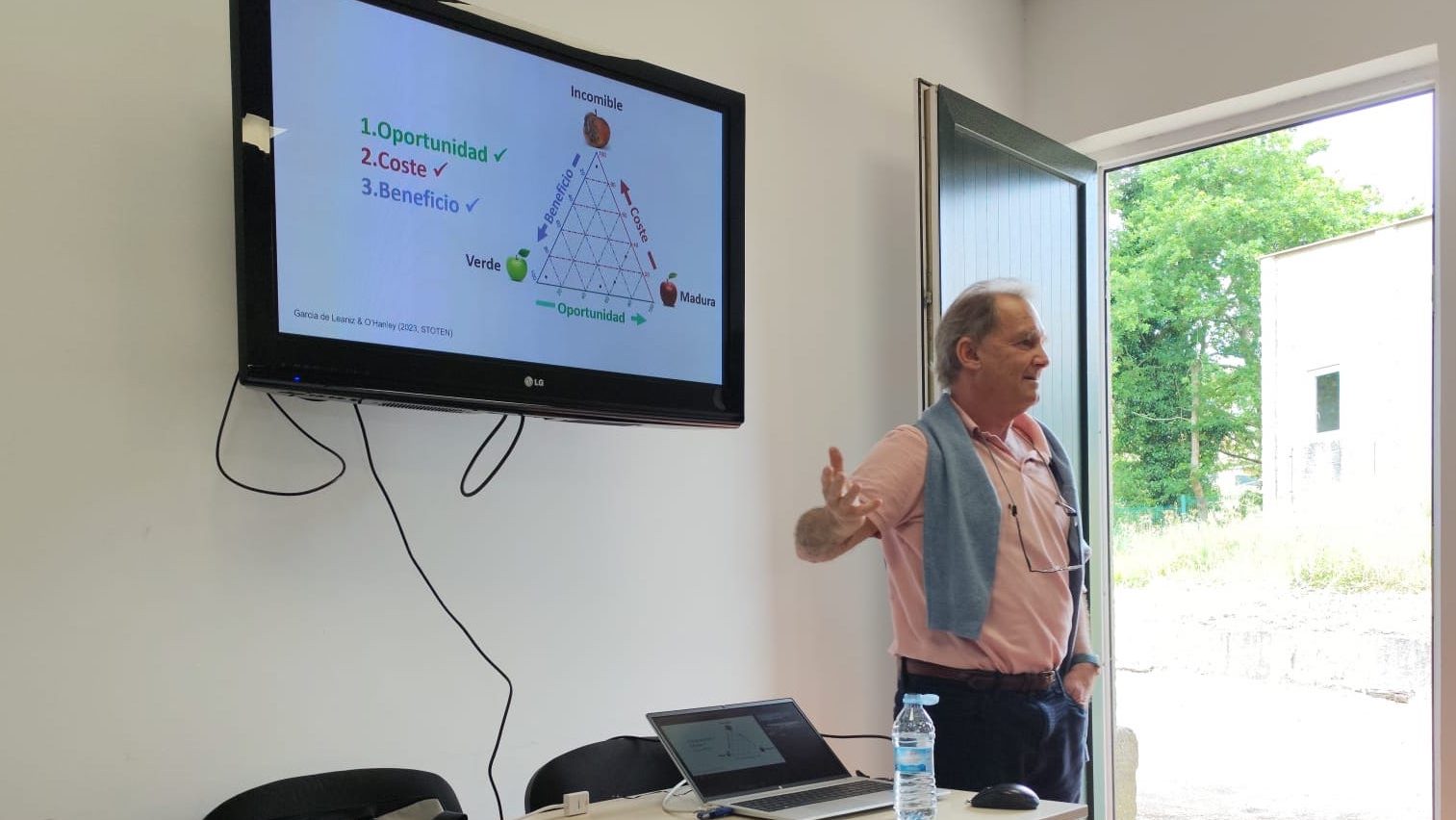

First, Carlos Garcia de Leaniz presented the project FREEFLOW and highlighted the key questions regarding river restoration that we aim to research and address throughout the project, in order to help restore 25,000 km of free-flowing rivers as mandated by the European Nature Restoration Law.

Carlos emphasised that there are still many unanswered questions about river restoration and barrier removal, and that this is a complex issue to tackle, with many uncertainties that can hinder restoration efforts and prevent effective outcomes. To ensure that river restoration efforts successfully contribute to reestablishing river connectivity, it is essential to prioritize barrier removal.

“It is impossible to remove all existing dams, so we must prioritize their removal in order to restore free-flowing rivers.”

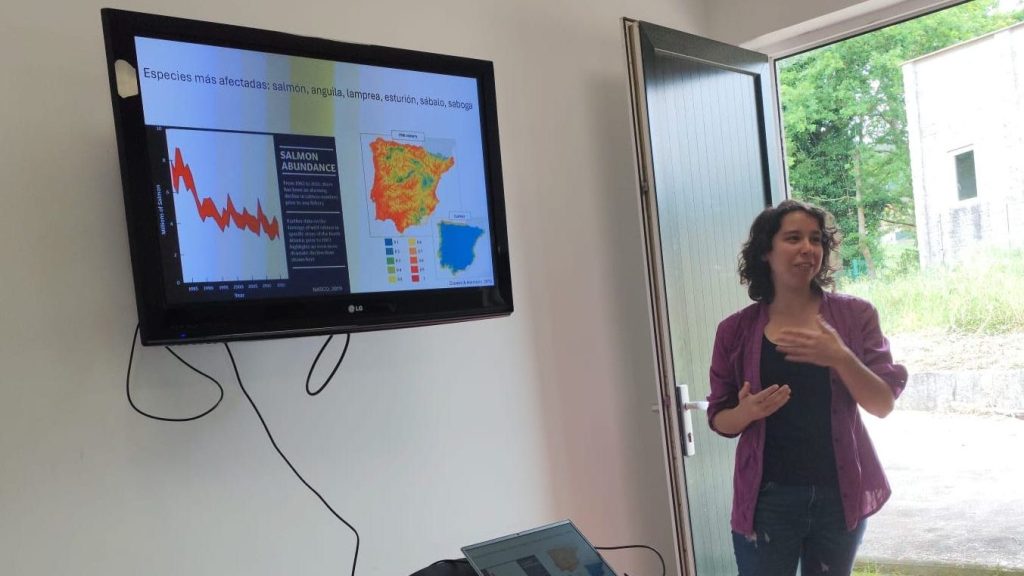

Next, Amaia Angulo Rodeles presented different approaches and methods for measuring river connectivity, considering barriers individually or collectively and at the catchment scale. These methods can be expanded to include factors such as population fragmentation of species, uncertainty in the number and location of river barriers, and the available budget for their removal or mitigation. She demonstrated that the removal of obstacles near the mouth of the river Bidasoa in Navarra allowed salmon to reach upstream habitats they had been unable to access for years.

Then, Alba Franco explained the various types of small-scale river barriers (weirs, culverts, ramps, riprap, etc) and their impacts on the fragmentation of both longitudinal and lateral river connectivity. She also presented how, within the FREEFLOW project, we will develop a rapid assessment tool to evaluate the impact of barriers, taking into account their fragmentation effects across all dimensions and processes of river connectivity (geomorphology, sediment transport, water quality, species mobility, etc.).

Nature Restoration Law (NRL)

EuroPean Commission 2024

“By the year 2030, restore at least 25 000 kms of Free-Flowing Rivers by the removal of primarily obsolete barriers and the restoration of associated floodplains and wetlands”

Following this, Gabriel Tedone emphasized the importance of barrier inventories and their use in river conservation, restoration, and hydrological planning, as well as the consequences of relying on incomplete barrier inventories. He also presented the various existing methods for barrier inventory and remote sensing techniques that enable the identification and characterization of river fragmentation remotely, using GIS data, LiDAR, AI, and geospatial modelling.

Finally, Pablo Caballero Javierre from the Consellería de Medio Ambiente (Xunta de Galicia) looked back at the history of fishing and the conservation of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in the iconic river Ulla —an area he has been involved with for over 30 years. He demonstrated how the first two weirs that salmon encounter when swimming upstream in the Ulla River (the Sinde and Couso weirs, in that order) almost completely blocked their passage to better upstream habitats and spawning grounds, which are essential for this emblematic and threatened species to complete its life cycle. Pablo showed that when weirs are removed or their impact is mitigated, salmon are able to swim upstream and are no longer caught in the fishing zones located just below the weirs. For example, since a flood destroyed the central part of the Sinde weir, very few salmon have been caught in that area, a trend also observed at Couso, since a vertical slot fishway was installed there.

“Even small dams like weirs fragment rivers and prevent the upstream migration of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar).”

Despite highlighting these small victories for fish species that must overcome such barriers and whose habitats are increasingly degraded, Pablo stressed the alarming state of salmon populations in the Ulla and across Galicia. Although there was a slight increase in numbers over the past decade, the trend in recent years has turned downward again, and populations are now reaching critically low levels.

At the end of the presentations, there were open questions and discussions about public opinion and social involvement regarding barrier removal. The debate addressed who holds legal responsibility for old weirs without concessions, as well as the procedures for dismantling infrastructure once its concession has expired.

Visit to Couso and Ximonde weirs

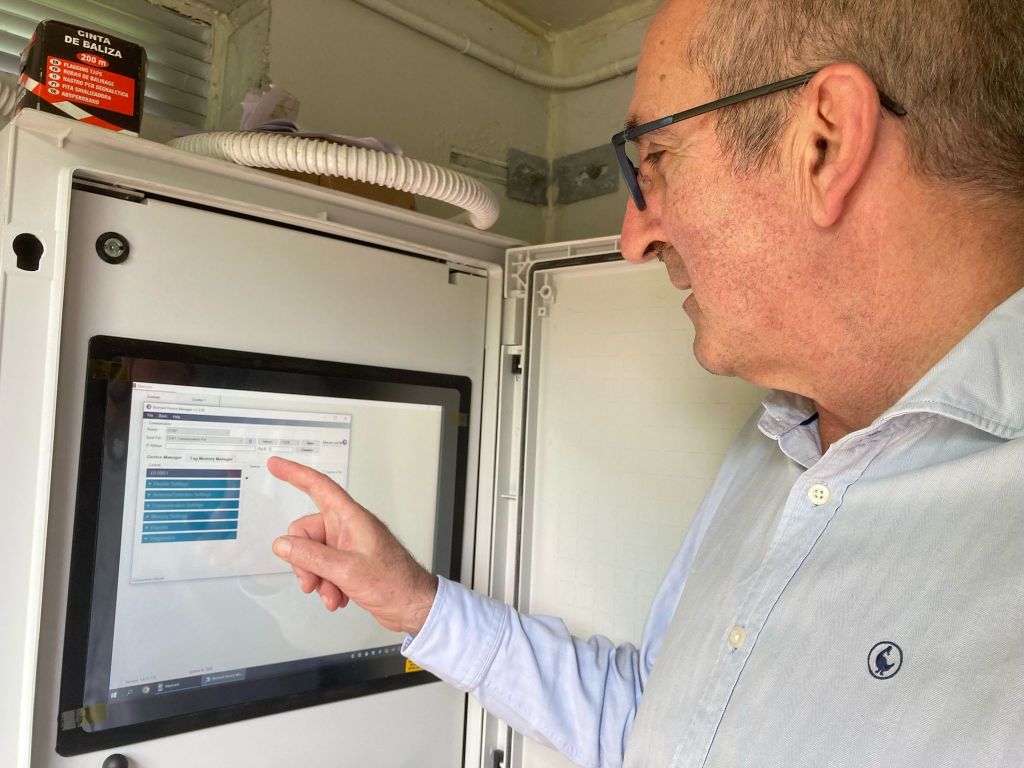

We continued the day by visiting the new fish counting facility at the salmon ladder of the Couso weir, the second obstacle that diadromous fish encounter when migrating upstream in the Ulla River. This new facility makes use of the fish ladder to monitor migratory fish populations and to gain a better understanding of their current status.

To conclude the day, we visited the Ximonde Fish Station, a biological research facility that has been studying the ichthyofauna of the Ulla River for decades, including populations of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), brown trout (Salmo trutta), sea trout (Salmo trutta), lamprey (Petromyzon marinus), eel (Anguilla anguilla), and other species during their upstream and downstream migrations through the Ximonde weir.

This weir features a Denil-type fish ladder to allow species such as salmon to ascend the barrier. For downstream migration, there is also a trap that enables the monitoring of smolts (juvenile salmon in the river) as they return to the sea after spawning and growing in the river.

The day also offered an opportunity for several former colleagues from the Ximonde Fish Station to reunite and fondly recall the time they spent working at the station, studying fish migration in the Ulla River.

We recommend visiting this small museum, which showcases the history of the ichthyofauna of the Ulla River, as well as its fishing, study, and conservation.